Lessons from Lutruwita

Tasmanian politics offers a taste of what might have been, and what could be next

May I especially recommend Tasmania in winter, when there’s no one around. I was lucky to spend a week there recently, arriving the day after their election. Snow on the plateau flying in, and fog rising off the lake where we went for a sauna. It's gorgeous and haunted, where the clearfelling continues centuries after the colonisers first studded the hills with stumps and graves. I bought a book called Uninnocent Landscapes that traces one of the more complicated early civilising journeys of the white man among the palawa. We saw platypus at river crossings and wombats on Maria Island, previously a prison.

But Tasmania, unlike WA an actual island within an island, also feels like a freezing little case study of an Australia that could have been. It’s small enough that all politics is pretty local, a pretty tiny petri-dish for political experimenting.

Heading towards the recent federal election, all the talk was of a potential hung Parliament and what a minority government might mean for key political issues. Obviously that’s not what happened, and we litigated previously some of the reasons for the Labor landslide, including a failure across the progressive movement to fully engage with the opportunities for a strong cross-bench with balance of power in the lower house. We’ve also talked about how the federal approval of the North West Shelf extension was locked in on election night, and how progressives misidentifying their real opponents may have gifted Labor more seats.

But in Tasmania, hung Parliaments is what they do now, disillusion with the major parties putting Labor on 10 seats and Liberals on 14 in the last term, with 18 needed to form majority government. Only the political science professor bleating about instability on Hobart talkback radio seemed concerned about a rinse and repeat after the election - while many seemed switched off entirely. I saw more wombats than corflutes the week after.

Walking through Hobart on a crisp and clear Sunday there was no indication of political intrigue in the frigid air - and no one volunteered to talk about it until I made them, which checks out. Having deliberately triggered a fresh election barely a year after the last one with a no confidence motion in the government, Labor appears to have been punished by Tasmanian voters, who swung to the Liberals by more than 3% despite returning a Parliament with unchanged seat totals for both major parties. Labor is once again outnumbered by cross-bench MPs, including five Greens, with the make-up of the new Parliament potentially more progressive due to the replacement of the more conservative of the five Independents, including three Jacquie Lambie Network MPs who all lost their seats.

As a result, despite the Liberals retaining the four seat advantage they held previously, with both major parties still well short of a majority it’s Labor who should be closer to forming government due to the larger progressive cross-bench. The five Greens and three progressive Independents would be enough to get Labor over the line - if only Labor would talk to them. Strangely, that’s exactly what Labor leader Dean Winter has refused to do - presumably, his adamant support for factory farming in Macquarie Harbour, the logging industry and a new AFL stadium while Tasmania suffers from familiar health and housing crises means the Greens are anathema.

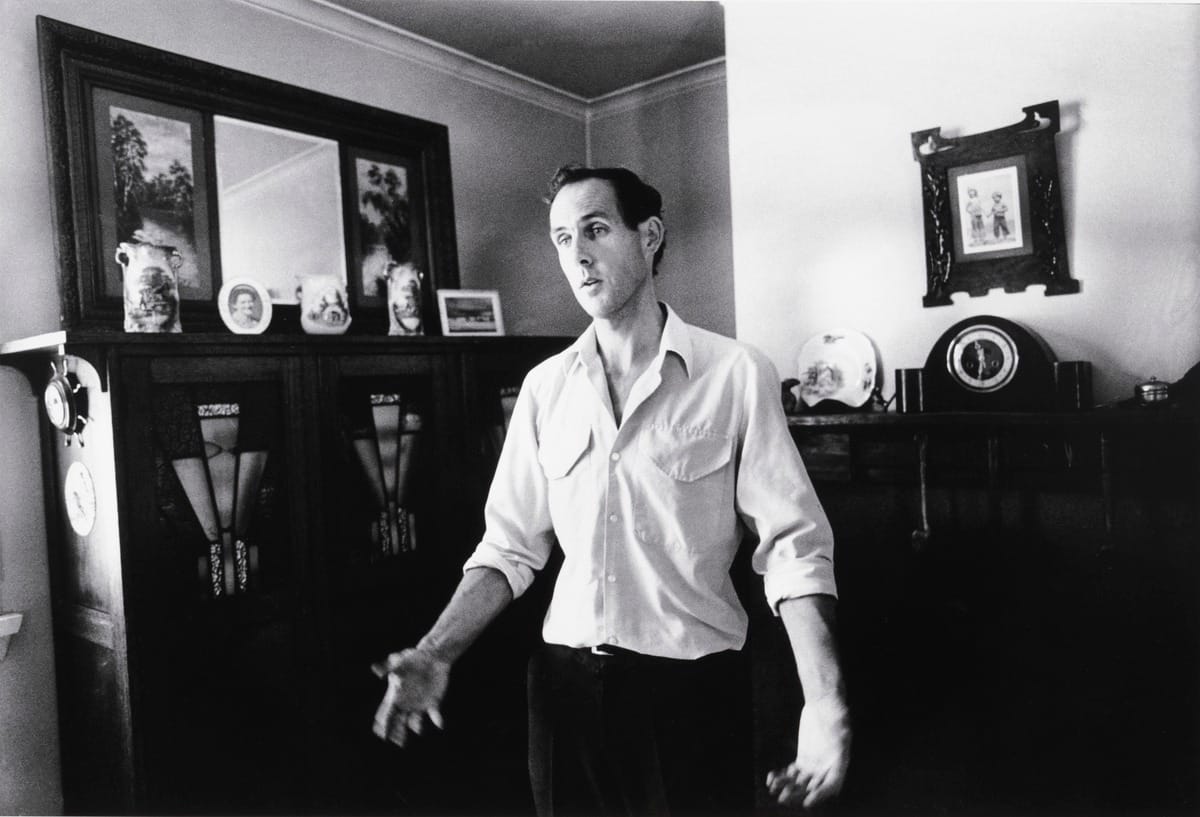

That’s certainly the view of former Greens leader and environmental legend Bob Brown, who I caught up with in Hobart.

“Labor and Dean Winter are boxing themselves into a hopeless position of self-disempowerment,” Bob reckons. “Labor is essentially a conservative party with the same policies as the Liberal party, in particular on the environment.”

Another hung Parliament with no immediate government emerging might seem like an ideal time to drive a hard bargain on key policies issues, but Bob cautions prudence for the new intake.

“The truth is that you’ve got to extract the concessions before you form government, because if you don't get those concessions and you don't come to an arrangement and you don't make it public - every word of it - then the government will again come under the influence of the corporate sector,” he tells me when we speak again by phone the other day.

“The challenge to the growing number of Independents in parliament is how they get together to use their combined numbers to influence the government in proportion to those numbers.”

For Bob, Tasmania is a harbinger of more powerful cross-benches to come. “I think they've got to look more at caucusing and more at talking with each other, more at making joint approaches to all the other parties.”

And that means progressive coalitions realising that they can form a more or less formal opposition of their own. “The reality is the Greens are there, and the reality is there's a growing number of independents, and the challenge is not to ask why but to get on with making good use of it. Why aren't they standing with the Greens? The fact is they aren't. That's the fact and so you deal with situations as they are.”

For Bob, this is personal. Despite his founding leadership of the party, when the Greens candidate for the federal seat of Franklin had to drop out, Bob threw his support behind the climate Independent Peter George, a former ABC journalist turned anti-salmon farm advocate. Bob’s partner even had a leading role with George’s campaign, which doubled down on a strong federal showing to win the state seat of Franklin last month.

“The independents, the teals if you like, are really an environmental organisation reacting on climate change and other environmental exigencies - which are influencing every one of us and which face the planet with a pretty hopeless future if we don't act on it - but they come from a conservative base and that's the difference,” he says.

“I think the wider the spectrum the electorate has to vote for, the more options, the healthier it is for democracy.

The spectrum in Tasmania is especially wide, thanks to their peculiar Hare-Clarke system of proportional representation in the lower house in which just five electorates furnish seven MPs each, meaning that Independents and Greens can all win in the same contest. But Bob also endorses a Tasmanian approach in more cut-throat electorates around the country.

“Look, I think that they necessarily do need to work together. I do think they at least have to be talking with each other, understanding each other and ready to get together against the Conservative old parties - Labor, Liberal and National - when the opportunity arises.”