This is World Heritage?

Reflections on the new Quarterly Essay from the source of emissions

It’s the first thing you see as you come round the first corner - the city on the plain. Like a new casino strip being constructed on a mud flat, the Perdaman fertiliser plant spreads across the horizon as the banks on either side of Burrup Rd open out. Further up to the left on an overlooking hill are more cranes, finishing off the expansion to Woodside’s Pluto gas processing plant. But it’s Perdaman that hits you like a knock to the head as you get to Murujuga.

I’ve been coming up here for less than four years, and it gets worse every time. On my first trips to Murujuga, the oldest, largest rock art gallery on Earth, with more than a million petroglyphs far older than Lascaux or the Pyramids, was more intact. It was only when you turned around from the ancient faces and animals on the boardwalk at Njanjarli (Deep Gorge), the site of some of the densest concentrations of rock art and the closest thing that Murujuga has to tourism infrastructure (apart from the Woodside Visitors Centre), that you were confronted with the clash of industry and culture. Now it’s literally the first thing you see. A wall of steel frames, cranes and massive silos that in the last light of day could almost look like mosques, apart from the visible emissions.

Funnily enough, there’s no sign of any industry at all in the photos of Murujuga on the UNESCO World Heritage website - instead, it just shows stunning shots of rock art and landscape on Murujuga, including some glowing drone shots of Njanjarli at sunset. But then, those photos were taken in 2020, although the listing was only approved in July this year. Five years ago Perdaman didn’t exist. Now it’s an alien civilisation squatting on the Burrup.

A new essay on the subject is out this week, the product of more than a year of investigation from respected former Four Corners journalist Marian Wilkinson looking at the hold that Woodside and the West Australian gas industry have over the country. I don’t agree with all Marian’s conclusions, in particular the relative emphasis she attributes to the various campaigns contesting the gas industry’s capture of state and federal politics (I think far more weight should be placed on the agency of Murujuga traditional custodians fighting against ongoing encroachment on their ngurra; they are, after all, the only ones who’ve beaten Woodside and the government in court.) But Wilkinson’s Quarterly Essay is a deep and intriguing dive for a national audience into a story that has remained far too uncovered in spite of its escalating political significance, and she speaks to a few people who provide unprecedented insight into the politics of industrial expansion in Australia (she also speaks to me about other stuff).

Heritage expert Heather Builth was a whistleblower at Juukan Gorge before she was hired by the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation (MAC) in 2021. She resigned at the end of her contract because of her despair at the impact of the Perdaman plant on Murujuga. “It wasn’t just four or five areas,” she tells Wilkinson. “It was a landscape, it was a waterscape, it was the Country. They didn’t realise how much it was going to be affected by this Perdaman build. It’s heartbreaking.”

MAC didn’t respond to my questions about the nature of any contractual arrangements between their organisation and Perdaman, but during my visit last week a large fleet of buses from their business arm Murujuga Commercial was parked each day in the middle of the Perdaman construction site. In a lengthy section on the complicated politics of Murujuga, Wilkinson sets out in sensitive detail the complexity of the hold that government and industry have over traditional custodians, whose native title was extinguished in a deal with the government that prevents them from objecting to industrial development over large parts of the Burrup Peninsula. The essay sets out with a nuanced ambivalence the manifestations of this interaction of state capture and cultural authority: in the results of contested rock art research, in community division, and in the deals that get done when industry inevitably expands further across the landscape.

As with World Heritage landscape, so with WA politics - what industry wants, it gets, and bring in the bulldozers for anything that gets in the way. Chris Tallentire was a Labor MP who dared to question the state government’s mantra that WA’s LNG exports are helping to decarbonise neighbouring Asian economies. “I can see that’s possible, but let’s get some real figures on it,” Wilkinson reports him telling Premier Roger Cook. Cook promised research to support the claim but it never materialised. This year, multiple attempts by independent analysts to access the WA government’s evidence via Freedom of Information request were refused on the grounds it would compromise cabinet confidentiality. Tallentire retired at the 2025 election, having been effectively frozen out by a WA Labor party whose party lines are written by the gas industry.

But the professional casualty Wilkinson details most closely is veteran Burrup archaeologist Dr Ken Mulvaney. He is not the only devoted rock art researcher to run afoul of the toxic politics that infects academia no less than any other WA field largely reliant on industry funding, but Mulvaney has more skin in the game than most after arriving on the Burrup with the WA Museum in 1980 for the construction of Woodside’s North West Shelf gas export plant. Mulvaney has previously described the experience of racing the bulldozers to document ancient rock art before it was crushed up to build the gas plant as “soul-destroying for the archaeologists and Traditional Owners.”

Last week I met Mulvaney back at the site of this historical destruction only to find the cultural erasure is still ongoing. “We recorded, in all over those two years, 9,200 petroglyphs,” Mulvaney told me, framed by flare towers and the mess of massive pipes that front Australia’s largest LNG hub. “We know that some 5,000 of those recorded images now lie under that plant. They're dust. They're destroyed. Bulldozers crushed them under their blades and their tracks, and they were dynamited.”

“Working in front of those bulldozers, I thought that would have been the last of the developments here,” Mulvaney reflected. “And I have literally for nearly 50 years been arguing against the appropriateness of industry continuing to be here, and yet I've continued to see it happen. And each time it’s said, ‘This will be the last. Never again.’ And then a new minister in Canberra, a new Minister in Perth comes in, and they sign off on another development.”

Indeed, much to my surprise, Mulvaney pointed to the very spot we were standing at the perimeter of the Woodside lease and announced that rock art he had documented here within the past two years had disappeared. “Where we're standing, there were pieces of rock art. They're not here now. It certainly wasn’t the public,” he told me, pointing to a line of nearby boulders placed, Mulvaney said, to block public access to beaches on the other side of the peninsula. “I do know that these were put in by Woodside. I'm assuming that the destruction of this outcrop was as a consequence of that action.”

“So, I get angry,” Mulvaney finished. “I get upset.” By the time we had visited the perimeter of the nearby Perdaman plant as well, this man who has spent more than half his life documenting industry eating away at the oldest, largest art gallery on Earth seemed close to heartbroken.

Of course, aside from the direct destruction beneath the construction of Woodside’s Burrup Hub, there is the long and contentious debate about its indirect erosion of Murujuga’s rock art. Wilkinson gives the saga a solid summary treatment, but the scandal enveloping the official government research program in recent months deserves its own extensive investigation, and may well get it with time.

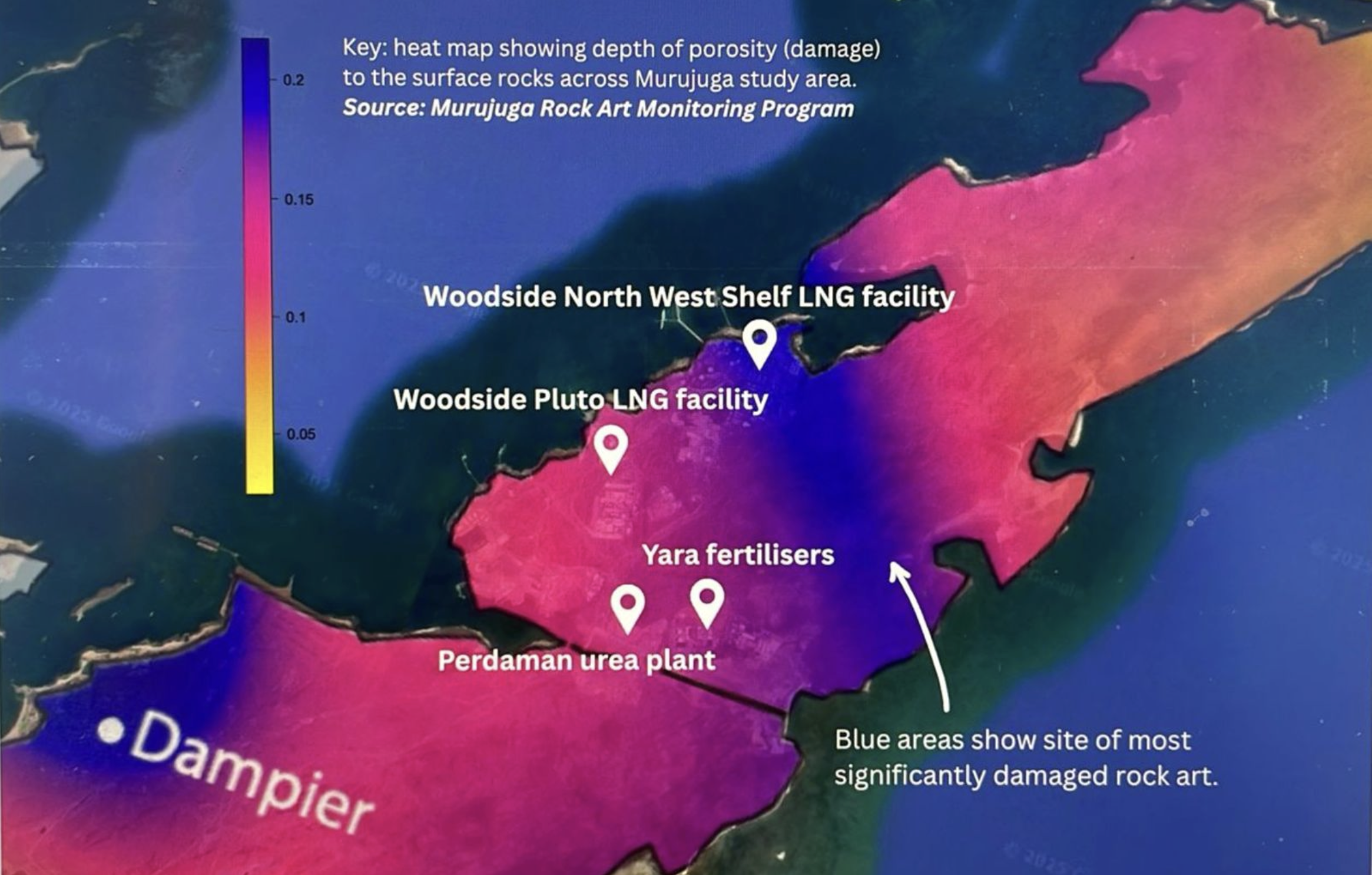

I will pull out just one element now as instructive - amidst all the accusations of cover ups, doctored science and government interference that attended the release of this year’s Murujuga rock art monitoring report, there was one thing the government was willing to allow. “There certainly has been, it would seem, an impact from previous industrial activity,” said Environment Minister Murray Watt on the 7am podcast this week. “There was a pretty dirty power station operating there at one point in time, and it’s quite likely that the emissions from that power station were having an impact. Thankfully, that’s not happening any more.”

Well, last week we tracked down this power station to two remnant smoke stacks standing near the shoreline in Dampier - a good 10 kilometres from the area the government report says that the rock art shows most sign of acid erosion. After satisfying ourselves that the Dampier power station hadn’t threatened to emit anything for some decades, we drove out to where the blue band on the government map indicates the most acute industrial impacts. And you’ll never guess what we found out there - Woodside’s North West Shelf facility, still pumping out a semi trailer’s worth of NOx and SOx emissions every day literally right on top of the most fragile rock art site. Also a lot closer to the eroded rock art than the disused Dampier power station were Woodside’s other gas plant and the Burrup’s two fertiliser plants, including Perdaman.

The WA government did once acknowledge the toxic potential of present industry on the Burrup. The original 2003 state agreement that formed the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation and split the Burrup between national park and industrial park also promised traditional custodians a cultural tourism centre that two decades later is still yet to be delivered. In a 2016 letter, then Premier Colin Barnett explained that the original site at Hearsons Cove, which remains a popular beach where I swam last week, “could present an unacceptable risk to public health and safety” due to the presence of two fertiliser plants barely a kilometre away. Instead, tourists now congregate at Njanjarli (Deep Gorge), where visitors have told me of vapor rising off the fertiliser plants across the road depositing as rain where they were viewing the rock art.

Samantha Walker is a Ngarluma traditional owner of Murujuga. Her grandfather is a senior Elder who refused to sign the 2003 agreement with the state government. On the phone to me this week, Walker reflected on how the likely influx of World Heritage tourists may experience Murujuga for the first time.

“That's sad if our visitors, our international friends, come over and see nothing but dirty industry when they expected to come and see the beauty of Murujuga. How would you feel? I would feel disgusted. I would feel devastated. I would feel so ripped off. But this has been preventable.”

“With World Heritage, the Country deserves to showcase the beauty that we still have out there, and it's a fight to try and keep it the way that it is right now. That Country is deteriorating quicker than any of us.”

“We need to take care of it, like I keep saying, preserve and protect it properly, and it takes the whole of Australia to do this. As traditional owners, we've been trying to do this for many, many, many decades.”

“We all need to turn our focus to how we can protect and preserve this beautiful piece of Country. We can have our elders sit down, tell stories to our friends that get off onto our shores. That's what true sharing is, Country and connecting. What are they going to connect to now? The horrible gas plants and the pollution that's coming out?”

Wilkinson’s section on Murujuga ends on a similar note: For a visitor admiring the celebrated petroglyphs at Deep Gorge in the Murujuga National Park, it is impossible not to wonder why, in 2025, a giant new fertiliser plant, fed by fossil fuels, emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases along with industrial pollution, is being built within a kilometre’s walk of this manifestation of human creative genius.

I think that wistful elegy is right, and I will go further. A great crime has been committed at Murujuga. I hope that those responsible are made to pay.